Flux is a refinement type checker plugin for Rust that lets you specify a range of correctness properties and have them be verified at compile time.

Flux works by extending Rust's types with refinements: logical assertions describing additional correctness requirements that are checked during compilation, thereby eliminating various classes of run-time problems.

You can try it on the online playground.

Better still, read the interactive tutorial, to learn how you can use Flux on your Rust code.

Installing and Running Flux

You can install and then run Flux either on a single file or on an entire crate.

Requirements

-

Rustup is required because Flux needs access to the source code of the Rust compiler, which we grab from rustup.

-

Nightly binary builds are avilable on GitHub Releases. If there is no binary available for your platform, you will need to build it from source.

-

z3 4.15 or later

You can download a binary for your platform from Z3 GitHub Releases. We recommend downloading the latest version, but older version should also work.

Note:

Make sure that the liquid-fixpoint and z3 binaries are in your $PATH.

Install

The only way to use Flux is to build it from source.

First you need to clone the repository

git clone https://github.com/flux-rs/flux

cd flux

To build the source you need a nightly version of rustc.

We pin the version using a toolchain file (more info here).

If you are using rustup, no special action is needed as it should install the correct rustc version and components based on the information on that file.

Next, run the following to build and install flux binaries

cargo xtask install

This will install two binaries flux and cargo-flux in your cargo home. These two binaries should be used

respectively to run Flux on either a single file or on a project using cargo. The installation process will

also copy some files to $HOME/.flux.

In order to use Flux refinement attributes in a Cargo project, you will need to add the following to your Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

flux-rs = { git = "https://github.com/flux-rs/flux.git" }

This will add the procedural macros Flux uses to your project; it is not a substitute for installing Flux, which must still be done.

Running on a File: flux

You can use flux as you would use rustc.

For example, the following command checks the file test.rs.

flux path/to/test.rs

The flux binary accepts the same flags as rustc.

You could for example check a file as a library instead of a binary like so

flux --crate-type=lib path/to/test.rs

Refinement Annotations on a File

When running flux on a file with flux path/to/test.rs, refinement annotations should be prefixed with flux::.

For example, the refinement below will only work when running flux which is intended for use on a single file.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[flux::spec(fn(x: i32) -> i32{v: x < v})] fn inc(x: i32) -> i32 { x - 1 } }

Running on a package: cargo-flux

See this an

Flux is integrated with cargo and can be invoked in a package as follows:

cargo flux

By default, Flux won't verify a package unless it's explicitly enabled in the manifest.

To do so add the following to Cargo.toml:

[package.metadata.flux]

enabled = true

Refinement Annotations on a Cargo Projects

Adding refinement annotations to cargo projects is simple. You can add flux-rs as a dependency in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

flux-rs = { git = "https://github.com/flux-rs/flux.git" }

Then, import attributes from flux_rs and add the appropriate refinement annoations.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use flux_rs::attrs::*; #[spec(fn(x: i32) -> i32{v: x < v})] fn inc(x: i32) -> i32 { x - 1 } }

A tiny example

The following example declares a function inc

that returns an integer greater than the input.

We use the nightly feature register_tool

to register the flux tool in order to

add refinement annotations to functions.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[flux::spec(fn(x: i32) -> i32{v: x < v})] pub fn inc(x: i32) -> i32 { x - 1 } }

You can save the above snippet in say test0.rs and then run

flux --crate-type=lib path/to/test0.rs

you should see in your output

error[FLUX]: postcondition might not hold

--> test0.rs:3:5

|

3 | x - 1

| ^^^^^

as indeed x - 1 is not greater than x as required by the output refinement i32{v: x < v}.

If you fix the error by replacing x - 1 with x + 1, you should get no errors

in the output (the output may be empty, but in this case no output is a good

thing).

Read these chapters to learn more about what you specify and verify with flux.

A note about the flux-driver binary

The flux-driver binary is a rustc

driver

(similar to how clippy works) meaning it uses rustc as a library to "drive"

compilation performing additional analysis along the way. Running the binary

requires dynamically linking a correct version of librustc. Thus, to avoid the

hassle you should never execute it directly. Instead, use flux or cargo-flux.

Editor Support

This section assumes you have installed cargo-flux.

Rust-Analyzer in VSCode

Add this to the workspace settings i.e. .vscode/settings.json

{

"rust-analyzer.check.overrideCommand": [

"cargo",

"flux",

"--workspace",

"--message-format=json-diagnostic-rendered-ansi"

]

}

Note: Make sure to edit the paths in the above snippet to point to the correct locations on your machine.

Configuration

Flux Flags

The flux binary accepts configuration flags in the format -Fname=value. For boolean flags, the

value can be one of y, yes, on, true, n, no, off, false. Alternatively, the value

can be omitted which will default to true. For example, to set the solver to cvc5 and enable

qualifier scraping:

flux -Fsolver=cvc5 -Fscrape-quals path/to/file.rs

For all available flags, see https://flux-rs.github.io/flux/doc/flux_config/flags/struct.Flags.html

Cargo Projects

When working with a Cargo project, some of the flags can be configured in the

[package.metadata.flux] table in Cargo.toml. For example, to enable query caching and set

cvc5 as the solver:

# Cargo.toml

[package.metadata.flux]

enabled = true

cache = true

solver = "cvc5"

Additionally, cargo flux searches for a configuration file called flux.toml with the same format

as the metadata table. The content of flux.toml takes precedence and it's merged with the

content of the metadata table. Note that the content of flux.toml will override the metadata

for all crates, including dependencies. This behavior is likely to change in the future as we figure

out what configurations make sense to have per package and which should only affect the current execution

of cargo flux.

You can see the format of the metadata in https://flux-rs.github.io/flux/doc/flux_bin/struct.FluxMetadata.html.

FLUXFLAGS Environement Variable

When running cargo flux, flags defined in FLUXFLAGS will be passed to all flux invocations,

for example, to print timing information for all crates checked by Flux:

FLUXFLAGS="-Ftimings" cargo flux

About Flux

Team

Flux is being developed by

Code

Flux is open-source and available here

Publications

- Lehmann, Nico, Adam T. Geller, Niki Vazou, and Ranjit Jhala. "Flux: Liquid types for rust." PLDI (2023)

- Lehmann, Nico, Cole Kurashige, Nikhil Akiti, Niroop Krishnakumar, and Ranjit Jhala. "Generic Refinement Types." POPL (2025)

Talks

Thanks

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation, European Research Council, and by generous gifts from Microsoft Research.

Limitations

This is a prototype! Use at your own risk. Everything could break and it will break.

Refining Types

Types bring order to code. For example, if a variable i:usize

then we know i is a number that can be used to index a vector.

Similarly, if v: Vec<&str> then we can be sure that v is a

collection of strings which may be indexed but of course,

not used as an index. However, by itself usize doesn't

tell us how big or small the number and hence the programmer

must still rely on their own wits, a lot of tests, and a dash

of optimism, to ensure that all the different bits fit properly

at run-time.

Refinements are a promising new way to extend type checkers with logical constraints that specify additional correctness requirements that can be verified by the compiler, thereby entirely eliminating various classes of run-time problems.

To begin, let's see how flux lets you refine basic or primitive

types like i32 or usize or bool with logical constraints that

can be checked at compile time.

Indexed Types

The simplest kind of refinement type in flux is a type that is indexed by a logical value. For example

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

i32[10] | The (singleton) set of i32 values equal to 10 |

bool[true] | The (singleton) set of bool values equal to true |

Flux Specifications

First off, we need to add some incantations that pull in the mechanisms for writing flux specifications as Rust attributes.

#![allow(unused)] extern crate flux_rs; use flux_rs::attrs::*;

Post-Conditions

We can already start using these indexed types to start writing (and checking)

code. For example, we can write the following specification which says that

the value returned by mk_ten must in fact be 10

#[spec(fn() -> i32[10])] pub fn mk_ten() -> i32 { 5 + 4 }

Push Play Push the "run" button in the pane above. You will see a red squiggle that and when you hover over the squiggle you will see an error message

error[...]: refinement type error

|

7 | 5 + 4

| ^^^^^ a postcondition cannot be proved

which says that that the postcondition might not hold which means

that the output produced by mk_ten may not in fact be an i32[10]

as indeed, in this case, the result is 9! You can eliminate the error

by editing the body to 5 + 4 + 1 or 5 + 5 or just 10.

Pre-Conditions

You can use an index to restrict the inputs that a function expects to be called with.

#[spec(fn (b:bool[true]))] pub fn assert(b:bool) { if !b { panic!("assertion failed") } }

The specification for assert says you can only call

it with true as the input. So if you write

fn test(){ assert(2 + 2 == 4); assert(2 + 2 == 5); // fails to type check }

then flux will complain that

error[FLUX]: precondition might not hold

|

12 | assert(2 + 2 == 5); // fails to type check

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

meaning at the second call to assert the input may not

be true, as of course, in this case, it is not!

Can you edit the code of test to fix the error?

Index Parameters and Expressions

Its not terribly exciting to only talk about fixed values

like 10 or true. To be more useful, flux lets you index

types by refinement parameters. For example, you can write

#[spec(fn(n:i32) -> bool[0 < n])] pub fn is_pos(n: i32) -> bool { if 0 < n { true } else { false } }

Here, the type says that is_pos

- takes as input some

i32indexed byn - returns as output the

boolindexed by0 < n

That is, is_pos returns true exactly when 0 < n.

We might use this function to check that:

pub fn test_pos(n: i32) { let m = if is_pos(n) { n - 1 } else { 0 }; assert(0 <= m); }

Existential Types

Often we don't care about the exact value of a thing -- but just

care about some properties that it may have. For example, we don't

care that an i32 is equal to 5 or 10 or n but that it is

non-negative.

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

i32{v: 0 < v} | The set of i32 values that positive |

i32{v: n <= v} | The set of i32 values greater than or equal to n |

Flux allows such specifications by pairing plain Rust types with assertions 1 that constrain the value.

Existential Output Types

For example, we can rewrite mk_10 with the output type

i32{v:0<v} that specifies a weaker property:

the value returned by mk_ten_pos is positive.

#[spec(fn() -> i32{v: 0 < v})] pub fn mk_ten_pos() -> i32 { 5 + 5 }

Example: absolute value

Similarly, you might specify that a function that computes the absolute

value of an i32 with a type which says the result is non-negative and

exceeds the input n.

#[spec(fn (n:i32) -> i32{v:0<=v && n<=v})] pub fn abs(n: i32) -> i32 { if 0 <= n { n } else { 0 - n } }

Combining Indexes and Constraints

Sometimes, we want to combine indexes and constraints in a specification.

For example, suppose we have some code that manipulates

scores which are required to be between 0 and 100.

Now, suppose we want to write a function that adds k

points to a score s. We want to specify that

- The inputs

sandkmust be non-negative, - the inputs

s + k <= 100, and - The output equals

s + k

#[spec(fn ({usize[@s] | s + k <= 100}, k:usize) -> usize[s + k])] fn add_points(s: usize, k: usize) -> usize { s + k } fn test_add_points() { assert(add_points(20, 30) == 50); assert(add_points(90, 30) == 120); // fails to type check }

Note that we use the @s to index the value of the s parameter,

so that we can

- constrain the inputs to

s + k <= 100, and - refine the value of the output to be exactly

usize[s + k].

EXERCISE Why does flux reject the second call to add_points?

Example: factorial

As a last example, you might write a function to compute the factorial of n

#[spec(fn (n:i32) -> i32{v:1<=v && n<=v})] pub fn factorial(n: i32) -> i32 { let mut i = 0; let mut res = 1; while i < n { i += 1; res = res * i; } res }

Here the specification says the input must be non-negative, and the

output is at least as large as the input. Note, that unlike the previous

examples, here we're actually changing the values of i and res.

Summary

In this post, we saw how Flux lets you

-

decorate basic Rust types like

i32andboolwith indices and constraints that let you respectively refine the sets of values that inhabit that type, and -

specify contracts on functions that state pre-conditions on the sets of legal inputs that they accept, and post-conditions that describe the outputs that they produce.

The whole point of Rust, of course, is to allow for efficient imperative sharing and updates, without sacrificing thread- or memory-safety. Next time, we'll see how Flux melds refinements and Rust's ownership to make refinements happily coexist with imperative code.

-

These are not arbitrary Rust expressions but a subset of expressions from logics that can be efficiently decided by SMT Solvers ↩

Ownership in Flux

Previously we saw how to refine basic Rust

types like i32 and bool with indices and constraints to

constrain the set of values described by those types. For instance, we

wrote the function assert function which can only be called with true

#[flux_rs::spec(fn (bool[true]))] fn assert(b: bool) { if !b { panic!("assertion failed"); } } fn test_assert() { assert(2 + 2 == 4); assert(2 + 2 == 5); // fails to type check }

The whole point of Rust, of course, is to allow for efficient imperative sharing and updates, via the clever type system that keeps an eye on the ownership of resources to make sure that aliasing and mutation cannot happen at the same time.

Next, lets see how Flux melds refinements and Rust's ownership mechanisms to make refinements pleasant in the imperative setting.

Exclusive Ownership

Rust's most basic form of sharing is exclusive ownership,

in which exactly one variable in a function has the right to

mutate a memory location. When a location is exclusively

owned, we can be sure that there are no other references

to it. Consequently, flux can update the type to precisely

track the value whenever the location is changed.

For example, consider the program

#[flux_rs::spec(fn () -> i32[3])] pub fn mk_three() -> i32 { let mut r = 0; // r: i32[0] r += 1; assert(r == 1); // r: i32[1] r += 1; assert(r == 2); // r: i32[2] r += 1; assert(r == 3); // r: i32[3] r }

The variable r has different types at each point inside mk_three.

It starts off as i32[0]. The first increment changes it to i32[1],

then i32[2] and finally, the returned type i32[3].

Exclusive Ownership and Loops

This exclusive ownership mechanism is at work in the factorial example

we signed off with previously

#[flux_rs::spec(fn (n:i32{0 <= n}) -> i32{v:n <= v})] pub fn factorial(n: i32) -> i32 { let mut i = 0; // i: i32[0] let mut r = 1; // r: i32[1] while i < n { // i: i32{v:0 <= v <= n} // r: i32{v:1 <= v && i <= v} i += 1; r = r * i; } r }

In the above code, i and r start off at 0 and 1 but then

flux infers (a story for another day) that inside the while-loop1

ihas typei32{v:0<=v && v < n}rhas typei32{v:1<=v && i <= v}

and hence, upon exit since i == n we get that the result is at least n.

Borrowing: Shared References

Exclusive ownership suffices for simple local updates

like in factorial. However, for more complex data,

functions must temporarily relinquish ownership to

allow other functions to mutate the data.

Rust cleverly allows this via the notion of borrowing using two kinds of references that give callee functions temporary access to memory location.

The simplest kind of references are &T

which denote read-only access to a value

of type T. For example, we might write abs to take

a shared reference to an i32

#[flux_rs::spec(fn (p: &i32[@n]) -> i32{v:0<=v && n<=v})] pub fn abs(p: &i32) -> i32 { let n = *p; if 0 <= n { n } else { 0 - n } }

Notice that the input type has changed. Now, the function

- accepts

p, a reference to ani32whose value isnas denoted by@n - returns an

i32that is non-negative and larger thann

The @ marks the n as a refinement parameter whose value

is automatically computed by flux during type checking.

Calling abs with a reference

So, for example, Flux can check the below code by automatically

determining that the refinement parameter at the call-site is 10.

pub fn test_abs() { let z = 10; assert(0 <= abs(&z)); assert(10 <= abs(&z)) }

Refinement Parameters

As an aside, we have secretly been using refinement parameters

like @n all along. For example, Flux automatically desugars

the signature fn(n:i32{0 <= n} -> ... that we wrote for factorial into

fn ({i32[@n] : 0 <= n}) -> i32{v:n <= v}

where @n is a refinement parameter that is implicitly determined

from the rust parameter n:i32. However, explicit parameters are

essential to name the value of what a reference points to.

In abs the rust parameter p names the reference but the

@n names the (input) value and lets us use it to provide

more information about the output of abs.

EXERCISE Flux is modular in that the

only information it knows about the

implementation of abs is the signature.

For example, suppose we change the output type

of abs to i32{v:0<=v}, that is, we remove the

n <= v conjunct. Can you predict which assert

will be rejected by flux?

Borrowing: Mutable References

References of type &mut T denote mutable references that can be

used to (read and) write or update the contents of a T value.

Crucially, Rust ensures that while there may be multiple read-only (shared)

references to a location, there is at most one active writeable (mutable)

reference at any point in time.

Flux exploits the semantics of &mut T to treat T as an invariant

of the underlying data. As an example, consider the following function

that decrements the value of a mutable reference while ensuring the

data is non-negative:

#[flux_rs::spec(fn(p: &mut i32{v:0 <= v}))] pub fn decr(p: &mut i32) { *p = *p - 1; }

Flux complains that

error[FLUX]: assignment might be unsafe

|

13 | *p = *p - 1;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^

as in fact, we may be writing a negative value into *p

for example, if the old value was zero. We can fix this

code by guarding the update with a test that ensures the

original contents are in fact non-zero

EXERCISE Can you modify the code for decr so that flux verifies it?

Aliased References

Flux uses Rust's borrowing rules to track invariants even when there may be aliasing. As an example, consider the function

#[flux_rs::spec(fn (bool) -> i32{v:0 <= v})] fn test_alias(z: bool) -> i32 { let mut x = 1; // x: i32[1] let mut y = 2; // y: i32[2] let r = if z { &mut x } else { &mut y }; // r: &mut i32{v:0 <= v} decr(r); *r }

The reference r could point to either x or y depending

on the (unknown) value of the boolean z. Nevertheless, Flux

determines that both references &mut x and &mut y point

to values of the more general type i32{v:0<=v} and hence,

infers r : &mut i32{v:0<=v} which allows us it to then call

decr with the reference and guarantee the result (after decr)

is still non-negative.

Invariants are not enough!

In many situations, we want to lend a value to another function

that actually changes the value's (refinement) type upon exit.

For example, consider the following function to increment

a reference to a non-negative i32

#[flux_rs::spec(fn (p: &mut i32{v:0 <= v}))] fn incr_inv(p: &mut i32) { *p += 1 } fn test_incr_inv() { let mut z = 10; incr_inv(&mut z); assert(z == 11); }

The only information that flux has about incr what

it says in its spec, namely, that p remains non-negative.

Flux is blissfully unaware that incr increments

the value of p, and it cannot prove that after the

call, z == 11 and hence, complains that assert

may fail even though it will obviously succeed!

Borrowing: Updatable References

To verify test_incr we need a signature for incr that says

that its output is indeed one greater2 than its input.

Flux extends Rust &mut T with the notion of updatable references

which additionally specify how the type is changed when

the function exits3, using an ensures clause that specifies

the modified type of the reference.

#[flux_rs::spec(fn(p: &mut i32[@n]) ensures p:i32[n+1])] fn incr(p: &mut i32) { *p += 1 }

The Flux signature refines the plain Rust one to specify that

pis a strong reference to ani32,- the input type of

*pisi32[n], and - the output type of

*pisi32[n+1].

With this specification, Flux merrily checks test_incr, by

determining that the refinement parameter @n is 10 and

hence, that upon return x: i32[11].

fn test_incr() { let mut z = 10; incr_inv(&mut z); assert(z == 11); }

Summary

To sum up, Flux exploits Rust's ownership mechanisms

to track properties of shared (&T) and mutable

(&mut T) references, and additionally uses (ensures)

clauses to specify when the type itself is changed by a call.

-

For those familiar with the term, these types are loop invariants ↩

-

Setting aside the issue of overflows for now ↩

-

Thereby allowing so-called strong updates in the type specifications ↩

Refining Structs

Previously, we saw how to slap refinements on existing built-in or primitive Rust types. For example,

i32[10]specifies thei32that is exactly equal to10andi32{v: 0 <= v && v < 10}specifies ani32between0and10.

Next, lets see how to attach refinements to user-defined types, so we can precisely define the set of legal values of those types.

Positive Integers

Lets start with an example posted on the flux gitHub:

how do you create a Positivei32? I can think of two ways:

struct Positivei32 { val: i32, }and structPositivei32(i32);but I do not know how to apply the refinements for them. I want it to be an invariant that the i32 value is >= 0. How would I do this?

With flux, you can define the Positivei32 type as follows:

#[refined_by(n: int)] #[invariant(n > 0)] struct Positivei32 { #[field(i32[n])] val: i32 }

In addition to defining the plain Rust type Positivei32,

the flux refinements say three distinct things.

- The

refined_by(n: int)tells flux to refine eachPositivei32with a specialint-sorted index namedn, - the

invariant(n > 0)says that the indexnis always positive, and, - the

fieldattribute onvalsays that the type of the fieldvalis ani32[n]i.e. is ani32whose exact value isn.

Creating Positive Integers

Now, you would create a Positivei32 pretty much as you might in Rust:

#[spec(fn() -> Positivei32)] fn mk_positive_1() -> Positivei32 { Positivei32 { val: 1 } }

and flux will prevent you from creating an illegal Positivei32, like

#[spec(fn() -> Positivei32)] fn mk_positive_0() -> Positivei32 { Positivei32 { val: 0 } }

A Constructor

EXERCISE Consider the following new constructor for Positivei32. Why does flux reject it?

Can you figure out how to fix the spec for the constructor so flux will be appeased?

impl Positivei32 { pub fn new(val: i32) -> Self { Positivei32 { val } } }

A "Smart" Constructor

EXERCISE Here is a different, constructor that should work

for any input n but which may return None if the input is

invalid. Can you fix the code so that flux accepts new_opt?

impl Positivei32 { pub fn new_opt(val: i32) -> Option<Self> { Some(Positivei32 { val }) } }

Tracking the Field Value

In addition to letting us constrain the underlying i32 to be positive,

the n: int index lets flux precisely track the value of the Positivei32.

For example, we can say that the following function returns a very specific Positivei32:

#[spec(fn() -> Positivei32[{n:10}])] fn mk_positive_10() -> Positivei32 { Positivei32 { val: 10 } }

(When there is a single index, we can just write Positivei32[10].)

Since the field val corresponds to the tracked index,

flux "knows" what val is from the index, and hence lets us check that

#[spec(fn() -> i32[10])] fn test_ten() -> i32 { let p = mk_positive_10(); // p : Positivei32[{n: 10}] let res = p.val; // res : i32[10] res }

Tracking the Value in the Constructor

EXERCISE Scroll back up, and modify the spec for new

so that the below code verifies. That is, modify the spec

so that it says what the value of val is when new returns

a Positivei32. You will likely need to combine indexes

and constraints as shown in the example add_points.

#[spec(fn() -> i32[99])] fn test_new() -> i32 { let p = Positivei32::new(99); let res = p.val; res }

Field vs. Index?

At this point, you might be wondering why, since n is the value of the field val,

we didn't just name the index val instead of n?

Indeed, we could have named it val.

However, we picked a different name to emphasize that the index is distinct from the field. The field actually exists at run-time, but in contrast, the index is a type-level property that only lives at compile-time.

Integers in a Range

Of course, once we can index and constrain a single field, we can do so for many fields.

For instance, suppose we wanted to write a Range type with two fields start and end

which are integers such that start <= end. We might do so as

#[refined_by(start: int, end: int)] #[invariant(start <= end)] struct Range { #[field(i32[start])] start: i32, #[field(i32[end])] end: i32, }

Note that this time around, we're using the same names for the index as the field names (even though they are conceptually distinct things).

Legal Ranges

Again, the refined struct specification will ensure we only create legal Range values.

fn test_range() { vec![ Range { start: 0, end: 10 }, // ok Range { start: 15, end: 5 }, // rejected! ]; }

A Range Constructor

EXERCISE Fix the specification of the new

constructor for Range so that both new and

test_range_new are accepted by flux. (Again,

you will need to combine indexes and constraints

as shown in the example add_points.)

impl Range { pub fn new(start: i32, end: i32) -> Self { Range { start, end } } } #[spec(fn() -> Range[{start: 0, end: 10}])] fn test_range_new() -> Range { let rng = Range::new(0, 10); assert(rng.start == 0); assert(rng.end == 10); rng }

Combining Ranges

Lets write a function that computes the union of two ranges.

For example, given the range from 10-20 and 15-25, we might

want to return the the union is 10-25.

fn min(x:i32, y:i32) -> i32 { if x < y { x } else { y } } fn max(x:i32, y:i32) -> i32 { if x < y { y } else { x } } fn union(r1: Range, r2: Range) -> Range { let start = min(r1.start, r2.start); let end = max(r2.end, r2.end); Range { start, end } }

EXERCISE Can you figure out how to fix the spec for min and max

so that flux will accept that union only constructs legal Range values?

Refinement Functions

When code get's more complicated, we like to abstract it into reusable

functions. Flux lets us do the same for refinements too. For example, we

can define refinement-level functions min and max which take int

(not i32 or usize but logical int) as input and return that as output.

defs! { fn min(x: int, y: int) -> int { if x < y { x } else { y } } fn max(x: int, y: int) -> int { if x < y { y } else { x } } }

We can now use refinement functions like min and max inside types.

For example, the output type of decr precisely tracks the decremented value.

impl Positivei32 { #[spec(fn(&Self[@p]) -> Self[max(1, p.n - 1)])] fn decr(&self) -> Self { let val = if self.val > 1 { self.val - 1 } else { self.val }; Positivei32 { val } } } fn test_decr() { let p = Positivei32{val: 2}; // p : Positivei32[2] assert(p.val == 2); let p = p.decr(); // p : Positivei32[1] assert(p.val == 1); let p = p.decr(); // p : Positivei32[1] assert(p.val == 1); }

Combining Ranges, Precisely

EXERCISE The union function that we wrote

above says some Range is returned, but nothing

about what that range actually is! Fix the spec

for union below, so that flux accepts test_union below.

impl Range { #[spec(fn(&Self[@r1], &Self[@r2]) -> Self)] pub fn union(&self, other: &Range) -> Range { let start = if self.start < other.start { self.start } else { other.start }; let end = if self.end < other.end { other.end } else { self.end }; Range { start, end } } } fn test_union() { let r1 = Range { start: 10, end: 20 }; let r2 = Range { start: 15, end: 25 }; let r3 = r1.union(&r2); assert(r3.start == 10); assert(r3.end == 25); }

Summary

To conclude, we saw how you can use flux to refine user-defined struct to track,

at the type-level, the values of fields, and to then constrain the sets of legal

values for those structs.

To see a more entertaining example, check out this code

which shows how we can use refinements to ensure that only legal Dates can be constructed

at compile time!

Refining Enums

Previously we saw how to refine structs to constrain the space

of legal values, for example, to define a Positivei32 or a Range struct where

the start was less than or equal to the end. Next, lets see how the same mechanism

can be profitably used to let us check properties of enums at compile time.

Failure is an Option

Rust's type system is really terrific for spotting all manner of bugs at compile time. However, that just makes it all the more disheartening to get runtime errors like

thread ... panicked at ... called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value

Lets see how to refine enum's like Option to

let us unwrap without the anxiety of run-time failure.

A Refined Option

To do so, lets define a custom Option type 1 that

is indexed by a bool which indicates whether or not

the option is valid (i.e. Some or None):

#[refined_by(valid: bool)] enum Option<T> { #[variant((T) -> Option<T>[{valid: true}])] Some(T), #[variant(Option<T>[{valid: false}])] None, }

As with std::option::Option, we have two variants

Some, with the "payload"TandNone, without.

However, we have tricked out the type in two ways.

- First, we added a

boolsorted index that aims to track whether the option isvalid; - Second, we used the

variantattribute to specify the value of the index for theSomeandNonecases.

Constructing Options

The definition above tells flux that Some(...)

has the refined type Option<...>[{valid: true}],

and None has the refined type Option<...>[{valid: false}].

NOTE When there is a single refinement index, we can skip the {valid:b}

and just write b.

#[spec(fn () -> Option<i32>[true])] fn test_some() -> Option<i32> { Option::Some(12) } #[spec(fn () -> Option<i32>[false])] fn test_none() -> Option<i32> { Option::None }

Destructing Options by Pattern Matching

The neat thing about refining variants is that pattern matching

on the enum tells flux what the variant's refinements are.

For example, consider the following implementation of is_some

impl<T> Option<T> { #[spec(fn(&Self[@valid]) -> bool[valid])] pub fn is_some(&self) -> bool { match self { Option::Some(_) => true, // self : &Option<..>[true] Option::None => false, // self : &Option<..>[false] } } }

Never Do This!

When working with Option types, or more generally,

with enums, we often have situations in pattern-match

cases where we "know" that that case will not arise.

Typically we mark those cases with an unreachable!() call.

With flux, we can do even more: we can prove, at compile-time, that those cases will never, in fact, be executed.

#[spec(fn () -> _ requires false)] fn unreachable() -> ! { assert(false); // flux will prove this is unreachable unreachable!(); // panic if we ever get here }

The precondition false ensures that the only way that

a call to unreachable can be verified is when flux can prove

that the call-site is "dead code".

fn test_unreachable(n: usize) { let x = 12; // x : usize[12] let x = 12 + n; // x : usize[12 + n] where 0 <= n if x < 12 { unreachable(); // impossible, as x >= 12 } }

Unwrap Without Anxiety!

Lets use our refined Option to implement a safe unwrap function.

impl <T> Option<T> { #[spec(fn(Self[true]) -> T)] pub fn unwrap(self) -> T { match self { Option::Some(v) => v, Option::None => unreachable(), } } }

The spec requires that unwrap is only called

with an Option whose (valid) index is true,

i.e. Some(...).

The None pattern is matched only when the index

is false which is impossible, as it contradicts

the precondition.

Hence, flux concludes that pattern is dead code

(like the x < 12 branch is dead code in the

test_unreachable above.)

Using unwrap

Next, lets see some examples of how to use refined options

to safely unwrap.

Safe Division

Here's a safe divide-by-zero function that returns an Option<i32>:

#[spec(fn(n:i32, k:i32) -> Option<i32>)] pub fn safe_divide(n: i32, k: i32) -> Option<i32> { if k > 0 { Option::Some(n / k) } else { Option::None } }

EXERCISE Why does the test below fail to type check?

Can you fix the spec for safe_divide so flux is happy

with test_safe_divide?

fn test_safe_divide() -> i32 { safe_divide(10, 2).unwrap() }

Smart Constructors Revisited

Recall the struct Positivei32

and the smart constructor we wrote for it.

#[refined_by(n: int)] #[invariant(n > 0)] struct Positivei32 { #[field(i32[n])] val: i32 } impl Positivei32 { #[spec(fn(val: i32) -> Option<Self>)] pub fn new(val: i32) -> Option<Self> { if val > 0 { Option::Some(Positivei32 { val }) } else { Option::None } } }

EXERCISE The code below has a function that

invokes the smart constructor and then unwraps

the result. Why is flux complaining? Can you fix

the spec of new so that the test_unwrap figure

out how to fix the spec of new so that test_new_unwrap

is accepted?

fn test_new_unwrap() { Positivei32::new(10).unwrap(); }

TypeStates: A Refined Timer

Lets look a different way to use refined enums.

On the flux zulip we were asked

if we could write an enum to represent a Timer

with two variants:

Inactiveindicating that the timer is not running, andCountDown(n)indicating that the timer is counting down fromnseconds.

Somehow using refinements to ensure that the timer can only

be set to Inactive when n < 1.

Refined Timers

To do so, lets define the Timer, refined with an int index that tracks

the number of remaining seconds.

#[flux::refined_by(remaining: int)] enum Timer { #[flux::variant(Timer[0])] Inactive, #[flux::variant((usize[@n]) -> Timer[n])] CountDown(usize) }

The flux definitions ensure that Timer has two variants

Inactive, which has aremainingindex of0, andCountDown(n), which has aremainingindex ofn.

Timer Implementation

We can now implement the Timer with a constructor and a method to set it to Inactive.

impl Timer { #[spec(fn (n: usize) -> Timer[n])] pub fn new(n: usize) -> Self { Timer::CountDown(n) } #[spec(fn (self: &mut Self[0]))] fn deactivate(&mut self) { *self = Timer::Inactive } }

Deactivate the Timer

Now, you can see that flux will only let us set_inactive

a timer whose countdown is at 0.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn test_deactivate() { let mut t0 = Timer::new(0); t0.deactivate(); // verifies let mut t3 = Timer::new(3); t3.deactivate(); // rejected } }

Ticking the Timer

Here is a function to tick the timer down by one second.

impl Timer { #[spec(fn (self: &mut Self[@s]) ensures self: Self)] fn tick(&mut self) { match self { Timer::CountDown(s) => { let n = *s; if n > 0 { *s = n - 1; } } Timer::Inactive => {}, } } }

EXERCISE Can you fix the spec for tick so that flux accepts the following test?

fn test_tick() { let mut t = Timer::new(3); t.tick(); // should decrement to 2 t.tick(); // should decrement to 1 t.tick(); // should decrement to 0 t.deactivate(); // should set to Inactive }

Summary

In this chapter, we saw how you refine an enum with indices, and then specify

the values of the indices for each variant. This let us, for example, determine

whether an Option is Some or None at compile time, and to safely unwrap

the former, and to encode a "typestate" mechanism for a Timer that tracks how

many seconds remain in a countdown, ensuring we only deactivate when the timer

has expired.

You can do various other fun things, like

- track the length of a linked list or

- track the set of elements in the list, or

- determine whether an expression is in normal form, or

- ensure the layers of a neural network are composed correctly.

-

In the chapter on extern specifications we will explain how to "retrofit" these refinements onto the existing

std::option::Optiontype. ↩

Opaque Types: Refined Vectors

While rustc has a keen eye for spotting nasty bugs at

compile time, it is not omniscient. We've all groaned in

dismay at seeing deployed code crash with messages like

panicked at 'index out of bounds: the len is ... but the index is ...'

Next, lets see how flux's refinement and ownership mechanisms let us write a refined vector API whose types track vector sizes and ensure --- at compile time --- that vector accesses cannot fail at runtime.

Refining Vectors ...

To track sizes, lets define a struct that

is just a wrapper around the std::vec::Vec

type, but with a refinement index that tracks

the size of the vector.

#[opaque] #[refined_by(len: int)] pub struct RVec<T> { inner: Vec<T>, }

... to Track their Size

As with other structs we're using refined_by

to index the RVec with an int value (that will represent

the vector's length.)

The idea is that

RVec<i32>[10]represents a vector ofi32size 10, andRVec<bool>{v:0 < v}represents a non-empty vector ofbool, andRVec<RVec<f32>[n]>[m]represents a vector of vectors off32of sizemand each of whose elements is a vector of sizen.

... but Opaquely

The opaque attribute tells flux that we're not

going to directly connect the len to any of

the RVec's fields' values.

This is quite unlike Positivei32 example

where the index held the actual value of the field,

or the Timer example where the

index held the value of the countdown.

Instead, with an opaque struct the idea is that the value

of the index will be tracked solely by the API for that struct.

Next, lets see how to build such an API for creating and

manipulating RVec, where the length is precisely tracked

in the index.

Creating Vectors

I suppose one must start with nothing: the empty vector.

#[trusted] impl<T> RVec<T> { #[spec(fn() -> RVec<T>[0])] pub fn new() -> Self { Self { inner: Vec::new() } } }

The above implements RVec::new as a wrapper around Vec::new.

The #[trusted] attribute tells flux to not check this code,

i.e. to simply trust that the specification is correct.

Indeed, flux cannot check this code.

If you remove the #trusted (do it!) then flux will

complain that you cannot access the inner field

of the opaque struct!

So the only way to use an RVec is to define a "trusted" API,

and then use that in client code, where for example, callers

of RVec::new get back an RVec indexed with 0 : the empty vector.

Pushing Values

An empty vector is a rather desolate thing.

To be of any use, we need to be able to push

values into it, like so

#[trusted] impl<T> RVec<T> { #[spec(fn(self: &mut RVec<T>[@n], T) ensures self: RVec<T>[n+1])] pub fn push(&mut self, item: T) { self.inner.push(item); } }

The refined type for push says that it takes a updatable reference to an RVec<T> of size n and, a value T

and ensures that upon return, the size of self is increased by 1.

Creating a Vector with push

Lets test that the types are in fact tracking sizes.

#[spec(fn () -> RVec<i32>[3])] fn test_push() -> RVec<i32> { let mut v = RVec::new(); // v: RVec<i32>[0] v.push(1); // v: RVec<i32>[1] v.push(2); // v: RVec<i32>[2] v.push(3); // v: RVec<i32>[3] v }

EXERCISE: Can you correctly implement the code

for zeros so that it typechecks?

#[spec(fn(n: usize) -> RVec<i32>[n])] fn zeros(n:usize) -> RVec<i32> { let mut v = RVec::new(); // v: RVec<i32>[0] let mut i = 0; while i <= n { v.push(0); // v: RVec<i32>[i] i += 1; } v }

Popping Values

Not much point stuffing things into a vector if we can't get them out again.

For that, we might implement a pop method that returns the last element

of the vector.

Aha, but what if the vector is empty? You could return an

Option<T> or since we're tracking sizes, we could

require that pop only be called with non-empty vectors.

#[trusted] impl<T> RVec<T> { #[spec(fn(self: &mut {RVec<T>[@n] | 0 < n}) -> T ensures self: RVec<T>[n-1])] pub fn pop(&mut self) -> T { self.inner.pop().unwrap() } }

Note that unlike push which works for any RVec<T>[@n], the pop

method requires that 0 < n i.e. that the vector is not empty.

Using the push/pop API

Now already flux can start checking some code, for example if you push two

elements, then you can pop twice, but flux will reject the third pop at

compile-time

fn test_push_pop() { let mut vec = RVec::new(); // vec: RVec<i32>[0] vec.push(10); // vec: RVec<i32>[1] vec.push(20); // vec: RVec<i32>[2] vec.pop(); // vec: RVec<i32>[1] vec.pop(); // vec: RVec<i32>[0] vec.pop(); // rejected! }

In fact, the error message from flux will point to exact condition that

does not hold

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { error[FLUX]: precondition might not hold | 24 | v.pop(); | ^^^^^^^ call site | = note: a precondition cannot be proved at this call site note: this is the condition that cannot be proved | 78 | #[spec(fn(self: &mut{RVec<T>[@n] | 0 < n}) -> T | ^^^^^ }

Querying the Size

Perhaps we should peek at the size of the vector

to make sure its not empty before we pop it.

We can do that by writing a len method that returns

a usize corresponding to (and hence, by indexed by)

the size of the input vector

#[flux_rs::trusted] impl<T> RVec<T> { #[spec(fn(&RVec<T>[@vec]) -> usize)] pub fn len(&self) -> usize { self.inner.len() } }

EXERCISE Can you fix the spec for len so that the code below

verifies, i.e. so that flux "knows" that

- after two

pushes, the value returned by.len()is exactly2, and - after two

pops the size is0again.

fn test_len() { let mut vec = RVec::new(); vec.push(10); vec.push(20); assert(vec.len() == 2); vec.pop(); vec.pop(); assert(vec.len() == 0); }

Random Access

Of course, vectors are not just stacks, they also allow random access to their elements which is where those pesky panics occur, and where the refined vector API gets rather useful.

Now that we're tracking sizes, we can require

that the method to get an element only be called

with a valid index less than the vector's size

impl<T> RVec<T> { #[spec(fn(&RVec<T>[@n], i: usize{i < n}) -> &T)] pub fn get(&self, i: usize) -> &T { &self.inner[i] } #[spec(fn(&mut RVec<T>[@n], i: usize{i < n}) -> &mut T)] pub fn get_mut(&mut self, i: usize) -> &mut T { &mut self.inner[i] } }

Summing the Elements of an RVec

EXERCISE Can you spot and fix the off-by-one error

in the code below which loops over the elements

of an RVec and sums them up? 1

fn sum_vec(vec: &RVec<i32>) -> i32 { let mut res = 0; let mut i = 0; while i <= vec.len() { res += vec.get(i); i += 1; } res }

Using the Index trait

Its a bit of an eyesore to to use get and get_mut directly.

Instead lets implement the Index and IndexMut

traits for RVec which allows us to use the [..]

operator to access elements

impl<T> std::ops::Index<usize> for RVec<T> { type Output = T; #[spec(fn(&RVec<T>[@n], i:usize{i < n}) -> &T)] fn index(&self, index: usize) -> &T { self.get(index) } } impl<T> std::ops::IndexMut<usize> for RVec<T> { #[spec(fn(&mut RVec<T>[@n], i:usize{i < n}) -> &mut T)] fn index_mut(&mut self, index: usize) -> &mut T { self.get_mut(index) } }

Summing Nicely

Now the above vec_sum example looks a little nicer

fn sum_vec_fixed(vec: &RVec<i32>) -> i32 { let mut res = 0; let mut i = 0; while i < vec.len() { res += vec[i]; i += 1; } res }

Memoization

Lets put the whole API to work in this "memoized" version of the fibonacci function which uses a vector to store the results of previous calls

pub fn fib(n: usize) -> i32 { let mut r = RVec::new(); let mut i = 0; while i < n { if i == 0 { r.push(0); } else if i == 1 { r.push(1); } else { let a = r[i - 1]; let b = r[i - 2]; r.push(a + b); } i += 1; } r.pop() }

EXERCISE Flux is unhappy with the pop at the end of the function

which returns the last value as the result: it thinks the vector

may be empty and so the pop call may fail ... Can you spot and fix

the problem?

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { error[FLUX]: precondition might not hold --> src/vectors.rs:40:5 | 40 | r.pop() | ^^^^^^^ }

Binary Search

As a last example, lets look at a simplified version of the

binary_search method from std::vec, into which

we've snuck a tiny little bug

pub fn binary_search(vec: &RVec<i32>, x: i32) -> Result<usize, usize> { let mut size = vec.len(); let mut left = 0; let mut right = size; while left <= right { let mid = left + size / 2; let val = vec[mid]; if val < x { left = mid + 1; } else if x < val { right = mid; } else { return Ok(mid); } size = right - left; } Err(left) }

Flux complains in two places

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { error[FLUX]: precondition might not hold --> src/vectors.rs:152:19 | 152 | let val = vec[mid]; | ^^^^^^^^ call site | = note: a precondition cannot be proved at this call site note: this is the condition that cannot be proved --> src/rvec.rs:189:44 | 189 | #[spec(fn(&RVec<T>[@n], usize{v : v < n}) -> &T)] | ^^^^^ error[FLUX]: arithmetic operation may overflow --> src/vectors.rs:160:9 | 160 | size = right - left; | ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ }

-

The vector access may be unsafe as

midcould be out of bounds! -

The

sizevariable may underflow asleftmay exceedright!

EXERCISE Can you the spot off-by-one and figure out a fix?

Summary

Well then. We just saw how Flux's index and constraint mechanisms combine with Rust's ownership to let us write a refined vector API that ensures the safety of all accesses at compile time.

These mechanisms are compositional : we can use standard

type machinery to build up compound structures and APIs from

simple ones, as we will see when we use RVec to implment

sparse matrices and a small

neural network library.

-

Why not use an iterator? We'll get there in due course! ↩

Const Generics

Rust has a built-in notion of arrays : collections of objects of

the same type T whose size is known at compile time. The fact that

the sizes are known allows them to be allocated contiguously in memory,

which makes for fast access and manipulation.

When I asked ChatGPT what arrays were useful for, it replied

with several nice examples, including low-level systems programming (e.g.

packets of data represented as structs with array-valued fields), storing configuration data, or small sets of related values (e.g. RGB values for a pixel).

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { type Pixel = [u8; 3]; // RGB values let pix0: Pixel = [255, 0, 127]; let pix1: Pixel = [ 0, 255, 127]; }

Compile-time Safety...

As the size of the array is known at compile time, Rust can make sure that we don't create arrays of the wrong size, or access them out of bounds.

For example, rustc will grumble if you try to make a Pixel with 4 elements:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { | 52 | let pix2 : Pixel = [0,0,0,0]; | ----- ^^^^^^^^^ expected an array with a fixed size of 3 elements, found one with 4 elements | | | expected due to this }

Similarly, rustc will wag a finger if you try to access a Pixel at an invalid index.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { | 54 | let blue0 = pix0[3]; | ^^^^^^^ index out of bounds: the length is 3 but the index is 3 | }

... Run-time Panic!

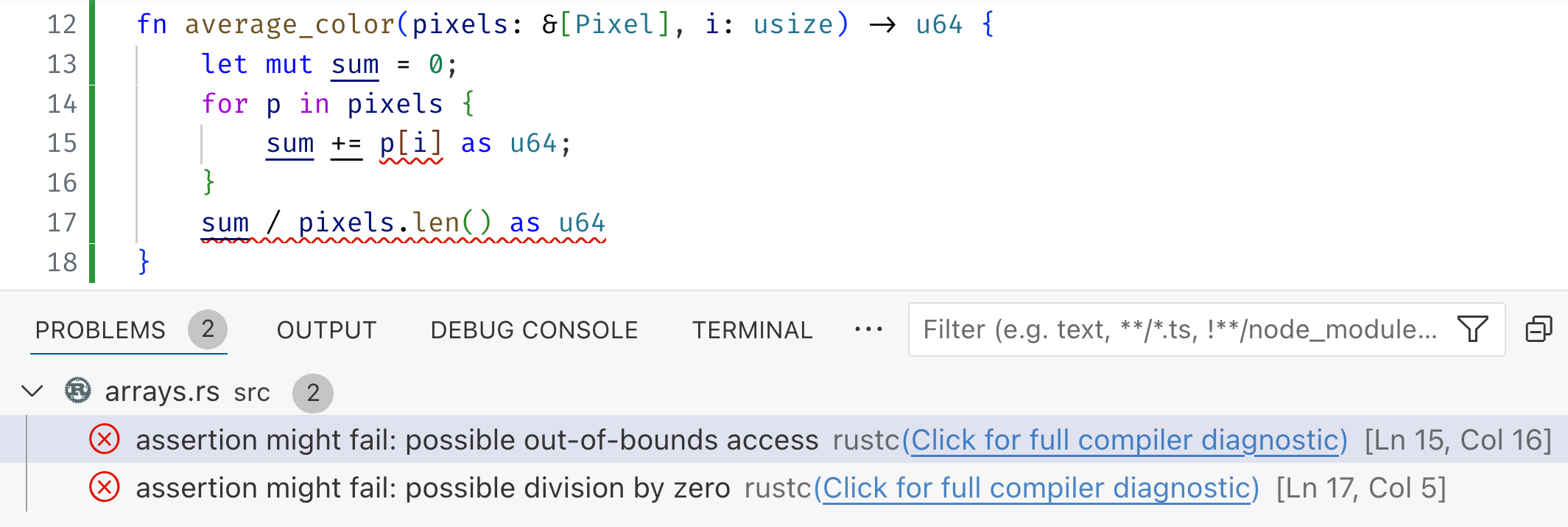

However, the plain type system works only upto a point. For example, consider the

following function to compute the average color value of a collection of &[Pixel]

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn average_color(pixels: &[Pixel], i: usize) -> u64 { let mut sum = 0; for p in pixels { sum += p[i] as u64; } sum / pixels.len() as u64 } }

Now, rustc will not complain about the above code, even though it may panic if

color is out of bounds (or of course, if the slice pixels is empty!).

For example, the following code

fn main() { let pixels = [ [255, 0, 0], [0, 255, 0], [0, 0, 255] ]; let avg = average(&pixels, 3); println!("Average: {}", avg); }

panics at runtime:

thread 'main' panicked ... index out of bounds: the len is 3 but the index is 3

Refined Compile-time Safety

Fortunately, flux knows about the sizes of arrays and slices. At compile time,

flux warns about two possible errors in average_color

- The index

imay be out of bounds when accessingp[i]and - The division can panic as

pixelsmay be empty (i.e. have length0).

We can fix these errors by requiring that the input

ibe a valid color index, i.e.i < 3andpixelsbe non-empty, i.e. have sizenwheren > 0

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[spec(fn(pixels: &[Pixel][@n], i:usize{i < 3}) -> u64 requires n > 0)] }

Const Generics

Rust also lets us write arrays that are generic over the size. For example,

suppose we want to take two input arrays x and y of the same size N and

compute their dot product. We can write

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn dot<const N:usize>(x: [f32;N], y: [f32;N]) -> f32 { let mut sum = 0.0; for i in 0..N { sum += x[i] * y[i]; } sum } }

This is very convenient because rustc will prevent us from calling dot with

arrays of different sizes, for example we get a compile-time error

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { | 68 | dot([1.0, 2.0], [3.0, 4.0, 5.0]); | --- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ expected an array with a fixed size of 2 elements, found one with 3 elements | | | arguments to this function are incorrect | }

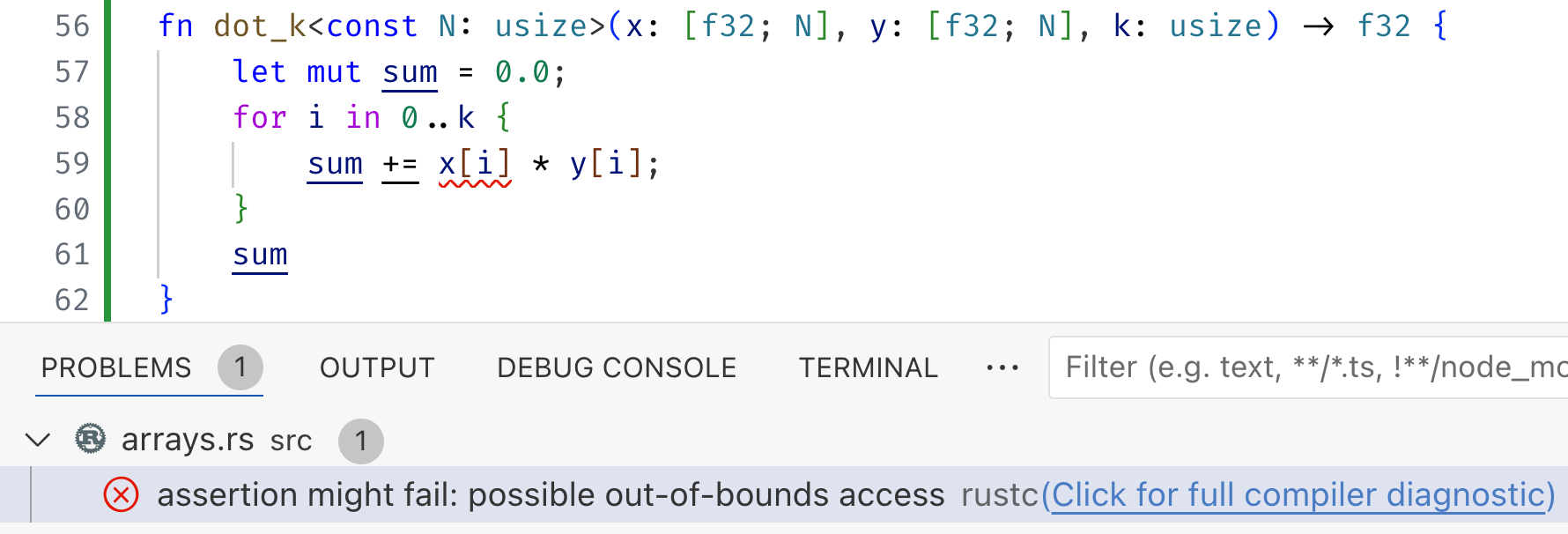

However, suppose we wanted to compute the dot product of just the first k elements

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn dot_k<const N:usize>(x: [f32;N], y: [f32;N], k: usize) -> f32 { let mut sum = 0.0; for i in 0..k { sum += x[i] * y[i]; } sum } }

Now, unfortunately, rustc will not prevent us from calling dot_k with k set to a value that is too large!

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { thread 'main' panicked at ... index out of bounds: the len is 2 but the index is 2 }

Yikes.

Refined Const Generics

Fortunately, flux understands const-generics as well!

First off, it warns us about the fact that the accesses with the index may be out of bounds.

We can fix it in two ways.

- The permissive approach is to accept any

kbut restrict the iteration to the valid elements

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn dot_k<const N:usize>(x: [f32;N], y: [f32;N], k: usize) -> f32 { let mut sum = 0.0; let n = if k < N { k } else { N }; for i in 0..n { sum += x[i] * y[i]; } sum } }

- The strict approach is to require that

kbe less than or equal toN

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[spec(fn(x: [f32;N], y: [f32;N], k:usize{k <= N}) -> f32)] fn dot_k<const N:usize>(x: [f32;N], y: [f32;N], k: usize) -> f32 { let mut sum = 0.0; for i in 0..k { sum += x[i] * y[i]; } sum } }

Do you understand why

(1) Adding the type signature moved the error from the body of dot_k into the call-site inside test?

(2) Then editing test to call dot_k with k=2 fixed the error?

Summary

Rust's (sized) arrays are great, and flux's refinements make them even better,

by ensuring indices are guaranteed to be within the arrays bounds. Const generics

let us write functions that are polymorphic over array sizes, and again, refinements

let us precisely track those sizes to prevent out-of-bounds errors!

Extern Specifications

#![feature(allocator_api)] #![allow(unused)] extern crate flux_rs; use flux_rs::{attrs::*, extern_spec}; use std::alloc::{Allocator, Global}; use std::mem::swap;

No man is an island.

Every substantial Rust code base will make use of external crates. To check properties of such code bases, Flux requires some way to reason about the uses of the external crate's APIs.

Let's look at how Flux lets you write assumptions1 about the behavior of those libraries via extern specifications (abbreviated to extern-specs) which can then let us check facts about the uses of the external crate's APIs.

To this end, flux lets you write extern-specs for

- Functions,

- Structs,

- Enums,

- Traits and their Impls.

In this chapter, we'll look at the first three, and then we'll see how the idea extends to traits and their implementations.

Extern Specs for Functions

As a first example, lets see how to write an extern spec for

the function std::mem::swap.

Using Extern Functions

Lets write a little test that creates to references and swaps them

pub fn test_swap() { let mut x = 5; let mut y = 10; std::mem::swap(&mut x, &mut y); assert(x == 10); assert(y == 5); }

Now, if you push the play button you should see that Flux cannot prove

the two asserts. The little red squiggles indicate it does not know that

after the swap the values of x and y are swapped to 10 and 5, as,

well, it has no idea about how swap behaves!

Writing Extern Specs

We can fill this gap in flux's understanding by providing

an extern-spec that gives flux a refined type

specification for swap

#[extern_spec] // UNCOMMENT THIS LINE to verify `test_swap` // #[spec(fn(x: &mut T[@vx], y: &mut T[@vy]) ensures x: T[vy], y: T[vx])] fn swap<T>(a: &mut T, b: &mut T);

The refined specification says that swap takes as input

two mutable references x and y that refer to values of

type T with respective indices vx and vy. Upon finishing,

the types referred to by x and y are "swapped".

Now, if you uncomment and push play, flux will verify test_swap as

it knows that at the call-site, vx and vy are respectively 5 and 10.

Features of Extern Spec Functions

Note two things about the extern_spec specification.

- First, up at the top, we had to import the

extern_specmacro, implemented in theflux_rscrate, - Second, importantly, we do not write an implementation for the function,

as that is going to be taken from

std::mem. Instead, we're just telling flux to use the (uncommented) type specification when checking clients.

Getting the Length of a Slice

Here is a function below that returns the first (well, 0th)

element of a slice of u32s.

fn first(slice: &[u32]) -> Option<u32> { let n = slice.len(); if n > 0 { Some(slice[0]) } else { None } }

EXERCISE Unfortunately, flux does not know what slice.len() returns, and

so, cannot verify that the access slice[0] is safe! Can you help

it by fixing the extern_spec for the method shown below?

You might want to refresh your memory about the meaning of

&[T][@n] by quickly skimming the previous chapter on the sizes of arrays

and slices.

#[extern_spec] impl<T> [T] { #[spec(fn(&[T][@n]) -> usize)] fn len(v: &[T]) -> usize; }

Extern Specs for Enums: Option

In the chapter on enums we saw how you can

refine enum types with extra indices that track extra information

about the underlying value. For example, we saw how to implement

a refined Option that is indexed

by a boolean that tracks whether the value is Some (and hence, safe

to unwrap)or None.

The extern_spec mechanism lets us do the same thing, but directly on

std::option::Option. To do so we need only

- write extern-specs for the enum definition that add the indices and connect them to the variant constructors,

- write extern-specs for the method signatures that let us use the indices to describe a refined API that is used to check client code.

Extern Specs for the Type Definition

First, lets add the bool index to the Option type definition.

#[extern_spec] #[refined_by(valid: bool)] enum Option<T> { #[variant(Option<T>[{valid: false}])] None, #[variant((T) -> Option<T>[{valid: true}])] Some(T), }

As you might have noticed, this bit is identical

to the refined version of Option that we saw in

the chapter on enums,

except for the #[extern_spec] topping.

Using the Type Definition

Adding the above "retrofits" the bool index directly

into the std::option::Option type. So, for example

we can write

#[spec(fn () -> Option<i32>[{valid: true}])] fn test_some() -> Option<i32> { Some(42) } #[spec(fn () -> Option<i32>[{valid: false}])] fn test_none() -> Option<i32> { None }

TIP: When there is a single field like valid

you can drop it, and just write Option<i32>[true]

or Option<i32>[false].

Extern Specs for Impl Methods

The extern specs become especially useful when we use them to refine

the methods that implement various key operations on Options.

To do so, we can make an extern_spec impl for Option, much like

we did for slices, back here.

#[extern_spec] impl<T> Option<T> { #[spec(fn(&Option<T>[@b]) -> bool[b])] const fn is_some(&self) -> bool; #[spec(fn(&Option<T>[@b]) -> bool[!b])] const fn is_none(&self) -> bool; #[spec(fn(Option<T>[true]) -> T)] const fn unwrap(self) -> T; }

The definition looks rather like the actual one,

except that it wears the #[extern_spec] attribute

on top, and the methods have no definitions, as we

want to use those from the extern crate, in this case,

the standard library.

Notice that the spec for

is_somereturnstrueif the inputOptionwas indeedvalid, i.e. was aSome(..);is_nonereturnstrueif the inputOptionwas notvalid, i.e. was aNone.

Using Extern Method Specifications

We can test these new specifications out in our client code.

fn test_opt_specs(){ let a = Some(42); assert(a.is_some()); let b: Option<i32> = None; assert(b.is_none()); }

Safely Unwrapping

Of course, we all know that we shouldn't directly use unwrap.

However, sometimes, its ok, if we somehow know that the value

is indeed a valid Some(..). The refined type for unwrap keeps

us honest with a precondition that tells flux that it should

only be invoked when the underlying Option can be provably

valid.

#[spec(fn (n:u32) -> Option<u8>)] fn into_u8(n: u32) -> Option<u8> { if n <= 255 { Some(n as u8) } else { None } } fn test_unwrap() -> u8 { into_u8(42).unwrap() }

EXERCISE The function test_unwrap above

merrily unwraps the result of the call into_u8.

Flux is unhappy and flags an error even though surely

the call will not panic! The trouble is that the "default"

spec for into_u8 -- the Rust type -- says it can

return any Option<i32>, including those that might

well blow up unwrap. Can you fix the spec for into_u8

so that flux verifies test_unwrap?

A Safe Division Function

Lets write a safe-division function, that checks if the divisor is non-zero before doing the division.

#[spec(fn (num: u32, denom: u32) -> Option<u32[num / denom]>)] pub fn safe_div(num: u32, denom: u32) -> Option<u32> { if denom == 0 { None } else { Some(num / denom) } }

EXERCISE The client test_safe_div shown below is certainly it is safe to

divide by two! Alas, Flux thinks otherwise: it cannot determine that output of

safe_div may be safely unwrapped. Can you figure out how to fix the specification

for safe_div so that the code below verifies?

pub fn test_safe_div() { let res = safe_div(42, 2).unwrap(); assert(res == 21); }

Extern Specs for Structs: Vec

Previously, we saw how to define a new type RVec<T>

for refined vectors and to write

an API that let us track the vector's size, and hence

check the safety of vector accesses at compile time.

Next, lets see how we can use extern_spec to implement

(most of) the refined API directly on structs like

std::vec::Vec which are defined in external crates.

Extern Specs for the Type Definition

As with enums we start by sprinkling refinement

indices on the struct definition. Since we want

to track sizes, lets write

#[extern_spec] #[refined_by(len: int)] #[invariant(0 <= len)] struct Vec<T, A: Allocator = Global>;

Extern Invariants

Note that we can additionally attach invariants to the struct

definition, which correspond to facts that are always true about

the indices, for example, that the len of a Vec is always non-negative.

Extern structs are Opaque

Unlike with enum, the extern_spec is oblivious

to the internals of the struct. That is flux

assumes that the fields are all "private", and so the

refinements must be tracked solely using the methods

used to construct and manipulate the struct.

The simplest of these is the one that births an empty Vec

#[extern_spec] impl<T> Vec<T> { #[spec(fn() -> Vec<T>[0])] fn new() -> Vec<T>; }

We can test this out by creating an empty vector

#[spec(fn () -> Vec<i32>[0])] fn test_new() -> Vec<i32> { Vec::new() }

Extern Specs for Impl Methods

Lets beef up our refined Vec API with a few more methods

like push, pop, len and so on.

We might be tempted to just bundle them together with new

in the impl above, but it is important to Flux that the

the extern_spec implementations mirror the original

implementations so that Flux can accurately match (i.e. "resolve")

the extern_spec method with the original method, and thus,

attach the specification to uses of the original method.

As it happens, push and pop are defined in a separate

impl block, parameterized by a generic A: Allocator, so

our extern_spec mirrors this block:

#[extern_spec] impl<T, A: Allocator> Vec<T, A> { #[spec(fn(self: &mut Vec<T, A>[@n], T) ensures self: Vec<T, A>[n+1])] fn push(&mut self, value: T); #[spec(fn(self: &mut Vec<T, A>[@n]) -> Option<T> ensures self: Vec<T, A>[if n > 0 { n-1 } else { 0 }])] fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<T>; #[spec(fn(self: &Vec<T, A>[@n]) -> usize[n])] fn len(&self) -> usize; #[spec(fn(self: &Vec<T, A>) -> bool)] fn is_empty(&self) -> bool; }

Constructing Vectors

Lets take the refined vec API out for a spin.

#[spec(fn() -> Vec<i32>[3])] pub fn test_push() -> Vec<i32> { let mut res = Vec::new(); // res: Vec<i32>[0] res.push(10); // res: Vec<i32>[1] res.push(20); // res: Vec<i32>[2] res.push(30); // res: Vec<i32>[3] assert(res.len() == 3); res }

Flux uses the refinements to type res as a 0-sized Vec<i32>[0].

Each subsequent push updates the reference's type

by increasing the size by one.

Finally, the len returns the size at that point, 3, thereby

proving the assert.

Testing Emptiness

EXERCISE Can you fix the spec for is_empty above so that the

two assertions below are verified?

fn test_is_empty() { let v0 = test_new(); assert(v0.is_empty()); let v1 = test_push(); assert(!v1.is_empty()); }

The Refined vec! Macro

The ubiquitous vec! macro internally allocates a slice

and then calls into_vec to create a Vec.

#[extern_spec] impl<T> [T] { #[spec(fn(self: Box<[T], A>) -> Vec<T, A>)] fn into_vec<A>(self: Box<[T], A>) -> Vec<T, A> where A: Allocator; }

EXERCISE Can you fix the extern_spec for into_vec so that

the code below verifies?

#[spec(fn() -> Vec<i32>[3])] pub fn test_push_macro() -> Vec<i32> { let res = vec![10, 20, 30]; assert(res.len() == 3); res }

Pop-and-Unwrap

Suppose we wanted to write a function that popped the last element of a non-empty vector.

#[spec(fn (vec: &mut Vec<T>[@n]) -> T requires 0 < n ensures vec: Vec<T>[n-1])] fn pop_and_unwrap<T>(vec: &mut Vec<T>) -> T { vec.pop().unwrap() }

EXERCISE Flux chafes because the spec for pop is too weak:

above does not tell us when the returned value is safe to unwrap.

Can you go back and fix the spec for fn pop so that pop_and_unwrap

verifies?

PopPop!

EXERCISE Finally, as a parting exercise, can you work out

why flux rejects the pop2 function below, and modify the spec

so that it is accepted?

#[spec(fn (vec: &mut Vec<T>[@n]) -> (T, T) ensures vec: Vec<T>[n-2] )] fn pop2<T>(vec: &mut Vec<T>) -> (T, T) { let v1 = pop_and_unwrap(vec); let v2 = pop_and_unwrap(vec); (v1, v2) }

Summary

Previously, we saw how to attach refined specifications for functions, structs and enums.

In this chapter, we saw that you can use the extern_spec

mechanism to do the same things for objects defined elsewhere,

e.g. in external crates being used by your code.

Next, we'll learn how to use extern_spec to refine traits

(and their implementations), which is key to checking idiomatic

Rust code.

-

We say assumption because we're presuming that the actual code for the library is not available to verify; if it was, you could of course actually guarantee that the library correctly implements those specifications. ↩

Traits and Associated Refinements

#![allow(unused)] extern crate flux_rs; extern crate flux_core; extern crate flux_alloc; use flux_rs::{attrs::*, extern_spec}; use std::ops::Range;

One of Rust's most appealing features is its trait system which lets us decouple descriptions of particular operations that a type should support, from their actual implementations, to enable generic code that works across all implementations of an interface.

Traits are ubiquitous in Rust code. For example,

-

an addition

x + yis internally represented asx.add(y)wherexandycan be values that implement theAddtrait, allowing for a uniform way to write+that works across all compatible types; -

an indexing operation

x[i]is internally represented asx.index(i)wherexcan be any value that implements theIndextrait, andia compatible "key", which allows for a standard way to lookup containers at a particular value; -

an iteration

for x in e { ... }becomeswhile let Some(x) = e.next() { ... }, where theecan be any value that implements theIteratortrait, allowing for an elegant and uniform way to iterate over different kinds of ranges and collections.

In this chapter, lets learn how traits pose some interesting puzzles for formal verification, and how Flux resolves these challenges with associated refinements.

First things First

To limber up before we get to traits, lets write a function to return (a reference to) the first element of a slice.

fn get_first_slice<A>(container: &[A]) -> &A { &container[0] }

The method get_first_slice works just

fine if you call it on non-empty slices,

but will panic at run-time if you try it on

an empty one

fn test_first_slice() { let s0: &[i32] = &[10, 20, 30]; let v0 = get_first_slice(s0); println!("get_first_slice {s0:?} ==> {v0}"); let s1: &[char] = &['a', 'b', 'c']; let v1 = get_first_slice(s1); println!("get_first_slice {s1:?} ==> {v1}"); let s2: &[bool] = &[]; let v2 = get_first_slice(s2); println!("get_first_slice {s2:?} ==> {v2}"); }

Catching Panics at Compile Time

You might recall from this previous chapter that Flux tracks the sizes of arrays and slices.

If you click the check button, you will see that flux

disapproves of get_first_slice

error[E0999]: assertion might fail: possible out of bounds access

|

13 | &container[0];

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^

Specifying Non-Empty Slices

EXERCISE Can you go back and add a flux spec for get_first_slice that says that the function

should only be called with non-empty slices? The spec should look something like the below, except

the ... should be a constraint over size.

#[spec(fn (container: &[A]{size: ...}) -> &A)]

When you are done, you should see no warnings in get_first_slice but you will get an error in

test_first_slice, precisely at the location where we call it with an empty slice, which you

can fix by commenting out or removing the last call...

A Trait to Index Values

Next, lets write our own little trait to index different kinds of containers1.

pub trait IndexV1<Idx> { type Output:?Sized; fn index(&self, index: Idx) -> &Self::Output; }

The above snippet defines a trait called IndexV1 that is parameterized by Idx: the

type used as the actual index. To implement the trait, we must specify

- The

Selftype for the container itself (e.g. a slice, a vector, hash-map, a string, etc.), - The

Idxtype used as the index (e.g. ausizeorStringkey, orRange<usize>, etc), and - The

Output: an associated type that describes what theindexmethod returns, and finally, - The

indexmethod itself, which takes a reference toselfand anindexof typeIdx, and returns a reference to theOutput.

A Generic, Reusable get_firstV1

We can now write functions that work over any type that implements the Index trait.

For instance, we can generalize the get_first_slice method, which only worked on slices,

to the get_firstV1 method will let use borrow the 0th element of any container that

implements Index<usize>.

fn get_firstV1<A, T>(container: &T) -> &A where T: ?Sized + IndexV1<usize, Output = A> { container.index(0) }

Indexing Slices with usize

To use the trait, we must actually implement it for particular types of interest.

Lets implement a method to index a slice by a usize value:

#[trusted] impl <A> IndexV1<usize> for [A] { type Output = A; fn index(&self, index: usize) -> &Self::Output { &self[index] } }

The above code describes an implementation where the

Selftype of the container is a slice[A];Idxtype of the index isusize;Outputreturned byindex()is a (reference to)A; andindex()is just a wrapper around the standard library's implementation.

Lets ignore the #[trusted] for now: it just tells flux to accept this code

without protesting about self[index] triggering an out-of-bounds error.

Testing get_firstV1

Sweet! Now that we have a concrete implementation for Index

we should be able to test it

fn test_firstV1() { let s0: &[i32] = &[10, 20, 30]; let v0 = get_firstV1(s0); println!("get_firstV1 {s0:?} ==> {v0}"); let s1: &[char] = &['a', 'b', 'c']; let v1 = get_firstV1(s1); println!("get_firstV1 {s1:?} ==> {v1}"); let s2: &[bool] = &[]; let v2 = get_firstV1(s2); println!("get_firstV1 {s2:?} ==> {v2}"); }

Click the run button. Huh?! No warnings??

Of course, the last one will panic.

But why didn't flux warn us about it, like it did with test_first_slice.

Yikes get_firstV1 is unsafe!

When we directly access a slice as in get_first_slice,

or test_first_slice, flux complains about the potential,

in this case, certain, out of bounds access.

But the indirection through get_firstV1 (and index) has

has laundered the out of bounds access, tricking

flux into unsoundly missing the run-time error!

We're in a bit of a pickle.

The Index trait giveth the ability to write generic

code like get_firstV1, but apparently taketh away the

ability to catch panics at compile-time.

Surely, there is a way to use traits without giving up on compile-time verification...

The Challenge: How to Specify Safe Indexing, Generically

Clearly we should not call get_firstV1 with empty slices.

The method get_firstV1 wants to access the 0-th element

of the container, and will crash at run-time if the 0th element

does not exist, as is the case with an empty slice.

But the puzzle is this: how do we specify

"the 0-th element exists" for any

generic container that implements Index?

Associated Refinements

Flux's solution to this puzzle is to borrow a page from Rust's own playbook.

Lets revisit the definition of the Index trait:

pub trait IndexV1<Idx> {

type Output:?Sized;

fn index(&self, index: Idx) -> &Self::Output;

}In the above, Output is an associated type for the Index trait that

specifies what the index method returns. For instance, in our implementation

of Index<usize> for slices [A], the Output is A.

Inspired this idea, Flux extends traits with the ability to specify

associated refinements that can describe the values accepted

and returned by the trait's methods.

Valid Indexes

Thus, we can extend the trait with an associated refinement

that specifies when an index is valid for a container.

Lets do so by defining the Index trait as:

#[assoc(fn valid(me: Self, index: Idx) -> bool)] pub trait Index<Idx: ?Sized> { type Output: ?Sized; #[spec(fn(&Self[@me], idx: Idx{ Self::valid(me, idx) }) -> &Self::Output)] fn index(&self, idx: Idx) -> &Self::Output; }

There are two new things in our new version of Index.

1. Declaration

First, the assoc attribute declares2 the associated refinement:

a refinement level function named valid, that

- takes as inputs, the

Selftype of the container and theIdxtype of the index, and - returns a

boolwhich indicates if theindexis valid for the container.

2. Use

Next, the spec attribute refines the index method to say that it should only be

passed an idx that is valid for the me container, where valid is the associated

refinement declared above. The notation Self::valid(me, idx) is a

way to refer to the valid associated refinement, similar to

how Self::Output is used to refer to the Output associated type.

A Safe (and Generic, Reusable) get_first

We can now write functions that work over any type that implements the Index trait,

but where flux will guarantee that index is safe to call. For example, lets revisit

the get_first method that returns the 0th element of a container.

// #[spec(fn (&T{ container: T::valid(container, 0) }) -> &A)] fn get_first<A, T>(container: &T) -> &A where T: ?Sized + Index<usize, Output = A> { container.index(0) }

Aha, now flux complains that the above is unsafe because we don't know that container

is actually valid for the index 0. To make it safe, we must add (uncomment!) the

flux specification in the line above. This spec says that get_first can only be called

with a container that is valid for the index 0.

Indexing Slices with usize

Lets now revisit that implementation of for slices using usize indexes.

#[assoc(fn valid(size: int, index: int) -> bool { index < size })] impl <A> Index<usize> for [A] { type Output = A; #[spec(fn(&Self[@me], idx:usize{ Self::valid(me, idx) }) -> &Self::Output)] fn index(&self, index: usize) -> &Self::Output { &self[index] } }

As with the trait definition, there are two new things in our implementation of Index for slices.

1. Implementation

First, we provide a concrete implementation of the associated refinement valid.

Recall that in flux, slices [A] are represented by their size at the refinement level.